Rwanda’s Vision 2020, launched in the year 2000, focused on guiding the nation on what to do in order to survive and regain its dignity. On the other hand, the current Vision 2050, appears to be more targeted on Rwanda’s aspiration to transform its economy into a high-income country and modernize the lives of all Rwandese. Forums on urban governance organized by the Partnership for African Social and Governance Research (PASGR) in collaboration with Institute of Policy Analysis and Research (IPAR-Rwanda) that brought together policy actors, non-state actors and research agencies in Rwanda on the nation’s policy culture provided interesting findings that explain the nation’s quest to urbanize. Part of the conclusive findings indicate that; countries such as Switzerland and Singapore have influenced the nation’s policy space and its development frameworks. A comparative analysis, as explored in some of the nation’s development frameworks such as the National Land use and Development Master Plan (2020-2050) and vision 2050, between Rwanda and nations that have emerged as small, safe, extremely rich and part of the most urbanized countries in the world with successful economic models explain where Rwanda draws its inspiration.

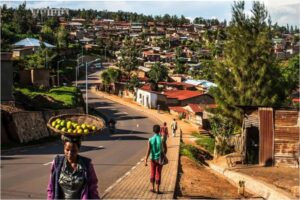

The country’s urbanisation model manifests itself in the form of but not limited to: major investments in modern physical infrastructure where roads are being used to open up human settlements for development; establishment of modern public housing where the government is striving to provide modern affordable housing whose production still favors the high income earning individuals in the country; creation of village mechanization centers aimed at rapidly mechanizing the agriculture value chain as proposed in the country’s National Land Use and Development plan and the establishment of secondary cities i.e. Musanze in Northern Province, Rubavu and Rusizi in Western Province, Muhanga and Huye in Southern Province and Nyagatare in Eastern Province. This urbanization model has been borrowed greatly from the Singapore model, which relies on secondary cities as additional engines for the country’s economic growth.

Conversations held in Rubavu secondary city sheds light on the emerging challenges accompanying the rapidly urbanizing cities. These challenges included concentration of services in small parts of the growing cities and inadequate provision of basic services infrastructure as compared to the number of people living and moving into the cities resulting to the fear of possible emergence and growth of uncontrolled development. This phenomenon by itself divulges the nature of urbanisation as an occurrence that organically springs up when factors favoring its growth are present. Contrary to the development models of majority of the developing countries, the Rwandan government policy space recognizes the citizens as key players in influencing and realizing the vision of the country. Concepts such as participatory planning approaches and socialism, are upheld in the governance process during the Umuganda sessions.

However, despite these laudable and visionary milestones, critics suggest that the nation has largely adopted a hyper-modernist approach that appears to forget the substantial social context of Rwanda and its realities. For instance, the notion of modernization leaves out aspects such as the informal economy that constitute traditional ways of life that have contributed to the growth of the country’s economy. A 2019 study by the World Bank on urbanization in Rwanda revealed that the nation had a “strict” definition of urbanization based on investment in structures that however understates the true pace and shape of urban land use transformation and densification. By sticking to the stringent definitions, the government might possibly neglect the emerging informal urban cluster, resulting in fragmented urban areas that may not support economies of scale or agglomeration. This is especially amplified through the failed housing project in Batsinda, where the low income earners are continually dispossessed by the market

This draws attention to two essential issues that Rwanda policy actors need to address. At the first level, it is important to interrogate the efficacy of public participation in Rwanda. Secondly, there is need to assess existing efforts to build grassroots capacity for meaningful engagement with the government and to provide alternative suggestions and models that can work. Such an assessment can be made by studying Kenya’s experiences with people-led planning, design and house development models and the uptake of the Delegated Management Model for water service delivery. These approaches demonstrate that, despite the challenges experienced in the nation’s urbanisation trends, the voice of the people at the grassroots in directing development can be very clear and specific.

It is recommended that, for Rwanda to shape its urbanization discourse towards the envisioned sustainable and inclusive country, there is need for plans to take into account the true pace and shape of urbanisation. The nation’s policy makers ought to consider broader rural-urban transformation of Rwanda’s economy rather than just the management of individual towns and cities. The nation also needs to invest heavily on strengthening its citizen’s participation in order to systematically harvest the rich knowledge that rests among them that could be essential in driving the urbanisation agenda.